Health, Psychedelics, Science

The Ongoing Battle for the Use of Psilocybin in Studies

Science vs law

The use of psychedelics for studies has been a topic for decades. These substances have shown to have therapeutic potential for a variety of mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and addiction. Despite its potential benefits, the use of psychedelics in research and therapy has faced significant legal barriers in many countries, including the EU.

Psilocybin holds a classification as a Schedule I drug by the UN. This classification implies that the production, supply, or possession of psilocybin is illegal. However, this categorization has posed significant challenges for researchers who aim to investigate its impact on the human body and mind. In recent years, though, an increasing number of researchers and organizations have been advocating for revisions to the EU’s drug laws. Their goal is to enable more research into the potential benefits of psilocybin.

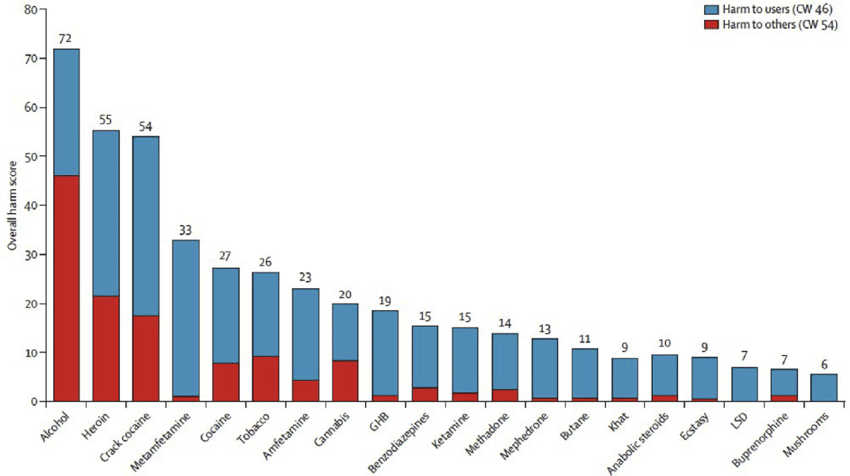

One of the main arguments for changing EU law is that psilocybin has been shown to be significantly less harmful than other Schedule I drugs. For example, heroin and cocaine are such Schedule I drugs. In fact, some studies have suggested that psilocybin may have a lower risk of addiction and other harmful effects than even alcohol. This has led many experts to call for a reclassification of psilocybin. This should make it easier for researchers to study its effects and potential benefits.

Normalized ratings of harm potential of psilocybin (mushroom) relative to other drugs

Figure 1: Normalized ratings of harm potential of psilocybin (“mushrooms”) relative to other drugs as rated by experts in the United Kingdom using on a multidimensional scale. Drugs are ranked by overall harm from left (most harmful) to right (least harmful), with harm to users (blue) and harm to others (red) shown separately.[1]

Scientists stand up for a right to research psychedelics

There are several researchers and groups in the EU advocating for the legality of psychedelics for research purposes. These groups include the Beckley Foundation, MAPS Europe, and the Psilocybin Society, among others. These groups believe that the benefits of research outweigh any potential risks. They believe that the substance has great potential for treating various mental health conditions. They are working to raise awareness about the benefits of psilocybin and to push for a change in EU law to allow for more research to be conducted. Some of the researchers of note include Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris, head of the Center for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London, Dr. David Nutt, former chief drug advisor to the UK government, and Dr. Amanda Feilding, founder and director of the Beckley Foundation.

Many researchers believe psychedelics, and especially psilocybin, hold significant potential in the field of medicine. They suggest it could effectively treat various mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD. However, they contend that the current restrictions on research regarding psychedelics hinder scientific progress and the development of effective treatments.

To foster more and improved psilocybin studies, these researchers actively advocate for changes in drug policies and increased research funding. By promoting its legal use for research purposes, these scientists aim to advance an evidence-based understanding of the drug and its impact on the human brain and behavior.

Final Statement

Despite these arguments, the ongoing battle for psychedelics and psilocybin’s use in research persists. Within the EU, numerous politicians and decision-makers remain skeptical regarding the substance’s potential benefits. They resist changing the law. Nonetheless, as an increasing amount of research unfolds, it becomes evident that psilocybin holds significant promise as a therapeutic tool. Consequently, the EU may soon find itself compelled to reevaluate its legislation pertaining to this substance.

[1] Matthew W. Johnson, Roland R. Griffiths, Peter S. Hendricks, Jack E. Henningfield: The abuse potential of medical psilocybin according to the 8 factors of the Controlled Substances Act. Neuropharmacology, Volume 142, 2018, Pages 143-166.